I was the Lead Product Manager for a product that failed. We saw 1 year of steady if not spectacular growth, after which the Product slowly plateaued. By year 3, it became clear to us that the product was unsustainable and so we made the tough decision to discontinue it and focus the company’s efforts on other ventures.

This was the toughest experience in my 10+ years of Product Management so far. Before that, I had helped to deliver several successful products that grew year-on-year, delighted our customers, and went from strength to strength, expanding in different markets and verticals. These successes didn’t come without their fair share of challenges, but our ultimate successes convinced me of my own skills as a Product Manager and I assumed that the rest of my career would continue on a similarly upward trajectory.

As you already know, I couldn’t have been more wrong but I learned a few invaluable lessons along the way that I wanted to share with the Product community, not only about this specific Product failure, but about the concept of failure in general and how I believe Product Managers should be approaching it.

So what happened? Why did the Product fail?

When the Product first started showing signs of ill-health (slow user base growth, increasing cost of acquisition, falling margins etc), I fell into an existential crisis of confidence. I questioned whether I had the Product chops to be in the role that I was in (a classic case of Imposter Syndrome), and blamed myself for its failings. I’ve always been good at taking ownership & responsibility over my area of work and the flip side of this normally good trait is that I blamed myself disproportionately for the declining health of our Product.

This was an emotional reaction to the danger signs that I was seeing. However, once we made the difficult decision to discontinue the product, I had no choice but to take some time & space away from the emotional mess of a failed venture and to do some introspection around why it had failed.

For those who are curious, I believe that our Product failed for two main reasons:

1. We didn’t build a true MVP

We invested a lot of time and effort upfront in the manufacturing of our product (it was a physical product, produced in a factory with a long manufacturing lead-time). This wasn’t because we were stupid or didn’t understand principles like MVP or the Lean startup methodology. We were well aware of these concepts as a software company, however this was our first proper foray into building a physical product and we found that we were not great at mitigating the risk that came with building a physical product, in the same ways that we did for software.

Our product had a software component as well and even with that, we over-complicated things. We built complex algorithms and systems to manage the logistical side of our business, where simple processes could have sufficed, at least in the early stages.

This didn’t cause the failure of the product itself – however, it increased complexity and our time to market, and probably went some way in diminishing the patience of our investors.

2. Changing market conditions

Probably the biggest lessons I learned from the failure of the Product was that you can’t fight the market. Within one month of our Product’s launch, the COVID-19 pandemic had reached its peak and countries around the world were going into lockdown. The resulting supply-chain crisis that occurred increased our cost of goods as the cost of the raw materials we used to make our products increased. This completely changed the unit economics of our product.

Several changes also occurred in the digital marketing landscape at the same time (ahem, iOS-14), which drastically increased our Cost of Acquisition.

The financial projections we had made based on certain assumptions therefore fell apart, due to conditions that were completely outside of our control.

This, more than any major failure on our part, is what accelerated the demise of a product that had consistently brought in great reviews from our customers, despite our internal challenges.

In the end, I realized that I was overestimating my importance and impact as a Product Manager. Though I absolutely should’ve been the one to come up with risk mitigation strategies and to promote the MVP approach more heavily within the company, there were some things that pushed our Product over the edge which nobody in the company could have foreseen or prevented.

The sunk-cost fallacy prevented us from making the right decision earlier, however we eventually realized that we were backing the wrong horse.

So, what happened next?

Where do I stand, 2 years on from this product failure and has my perspective changed on failure as a Product Manager?

Failure as a part of the process

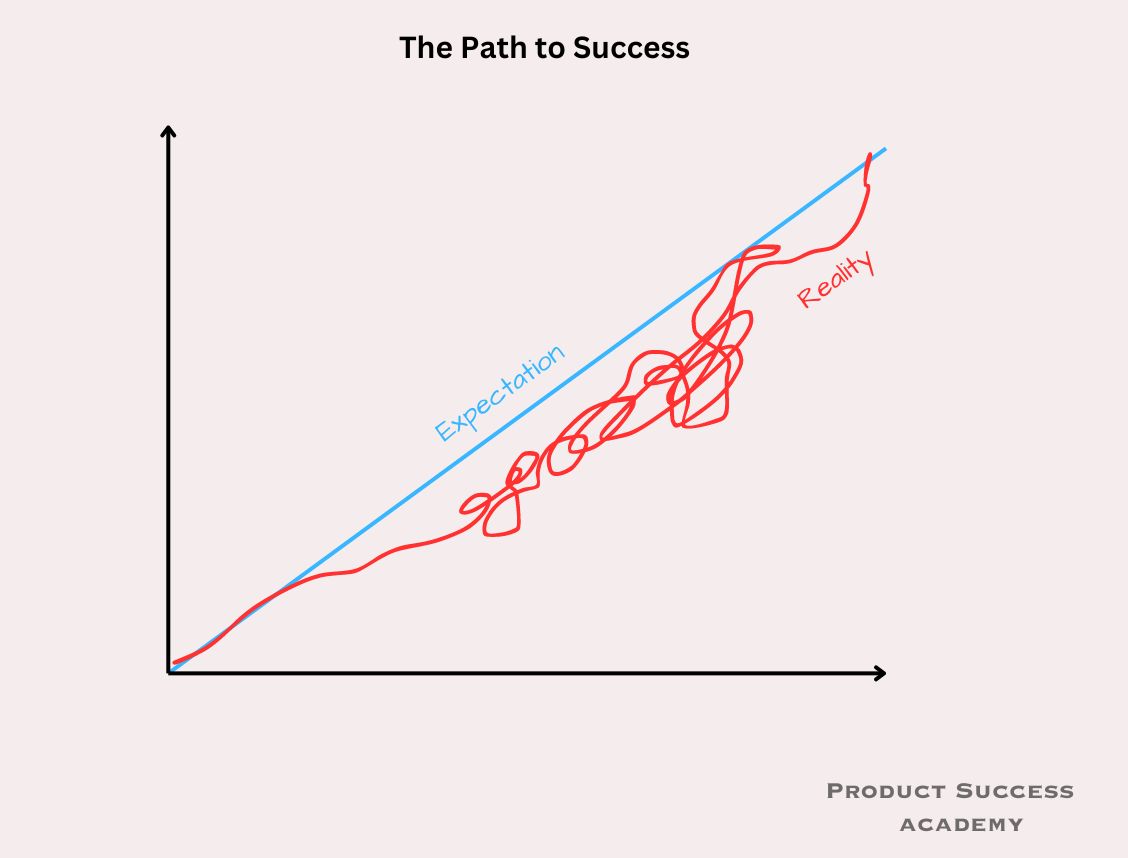

Though it took me some time to get there, I can now say that I look at the concept of failure entirely differently. In my naivety, I took my one failed Product experience rather personally. However, the more I learned about what prominent tech and business leaders have had to say about failure, the more convinced I am that failure is an inevitable ‘part of the process’ in the road to success.

Let’s take the Amazon Fire Phone as an example.

If like me, you had no idea what this was, that’s because this is one of Amazon’s most spectacular examples of failure. Amazon eventually wrote off its $170 million investment in the product and discontinued it. A product which was meant to be a competitor to the iPhone proved that it could not compete. Amazon’s history is littered with examples of other such failures, from its ‘Destinations’ project to Amazon Wallet.

I know what you’re thinking – not everyone is an Amazon and can afford to lose out on several million dollars worth of investments. I agree, however it’s not really about how much you can afford to lose – it’s more about Amazon’s attitude towards failure and how true innovation stems from it. Jeff Bezos has talked about the inextricable link between failure and innovation, saying that ‘failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment.”

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings has a similar approach and recently shocked the world by saying that Netflix had too many successful series lately. He said that ‘“our hit ratio is way too high right now. So, we’ve canceled very few shows … I’m always pushing the content team: We have to take more risk; you have to try more crazy things. Because we should have a higher cancel rate overall.” I did a double take when I read this. Does he really want the cancellation rate of new series on Netflix to be higher? Ie he wants more shows to fail? Turns out, he does and his logic is that if their cancellation rate is too low, that is a sign of a lack of innovation.

This approach has been taken a step further by renowned entrepreneur Steven Bartlett, who recently hired a “Head of Failure & Experimentation” for his organization, whose sole purpose it is to drive up their rate of failure. “Those that fail the fastest, get the most feedback, because failure is feedback and feedback is knowledge and knowledge is power”, he says. This is the approach that resonated with me the most. I definitely don’t have several million dollars to spend on ‘experimental’ ventures that may fail, and not every organization you may work in as a Product Manager will have the budget of an Amazon or a Netflix. However, what you can do is approach every endeavor of your life as a quest to gain feedback and learnings. The more you can learn from each failure, the better prepared you will be to eventually succeed.

This is an important lesson for Product Managers, who have been told countless times that knowing how to ‘fail fast’ and how to ‘pivot’ is an important skill in Product Management. The idea is to stop fearing ‘failure’, and instead to seek learnings from it and move forward.

That is where I’m at today. I will not set out with the explicit intention of failing – of course, nobody should, but I will not look at failure as an end destination ; a sad indictment of my shortcomings or weaknesses. Instead, I will look to use failure as a learning opportunity in the knowledge that it is very much a part of the process.

Leave a Reply